10 years of measuring sedentary behaviour and physical activity in Canada

November 27, 2017

Sitting on a ticking time bomb: managing type 2 diabetes in a sitting-centric world

January 30, 2018Today’s post comes from Dr Eun-Young Lee. More on Dr Lee can be found at the bottom of this post.

New Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for the Early Years were launched in November 20171. The new guidelines include general and specific recommendations for three movement behaviours, namely, physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep, for three different age groups (i.e., infants, toddlers, and preschoolers). For toddlers (aged 1 to 2 years) in particular, the specific recommendations include: ≥ 180 minutes of total physical activity spread throughout the day, including some energetic play or moderate-to vigorous-intensity physical activity (MVPA), zero screen time (for those aged 12-23 months) or ≤ 1 hour of screen time per day (ages 24-35 months), and 11-14 hours of sleep per 24-hour period.1

With the recent release of the new guidelines, determining the proportion of children who meet or do not meet the guidelines can 1) inform the research and development of appropriate preventive strategies and 2) aid the informed allocation of limited public resources. Furthermore, examining associations between meeting or not meeting guidelines and health indicators can help to validate the new recommendations to support guideline adoption. Using data from the Parents’ Role in Establishing healthy Physical activity and Sedentary behaviour habits (PREPS), this study was first to investigate the proportions of toddlers meeting the new guidelines. This study also investigated whether meeting the new guidelines were associated with adiposity among toddlers. In 151 toddlers (M age = 19 months old; 53% of boys), physical activity was objectively measured using ActiGraph accelerometers while screen time and sleep were measured via parental-report using the PREPS questionnaire. Toddlers’ height and weight were objectively measured by public health nurses and body mass index (BMI) z-scores were calculated based on World Health Organization growth standards.

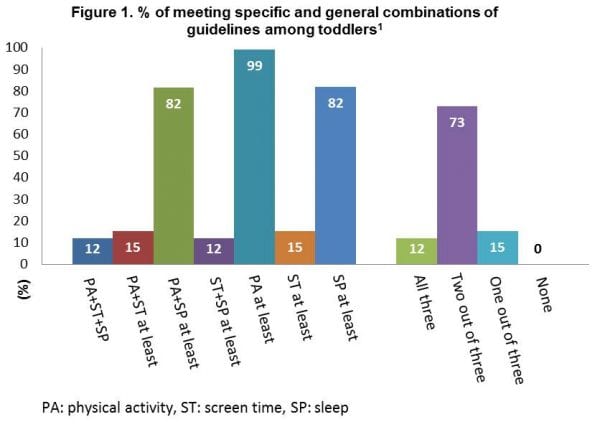

Overall, only 12% met all three recommendations within the new guidelines (Figure 1). The low adherence rate to the overall guidelines was largely driven by a small number of toddlers meeting the screen time recommendation. Specifically, though the majority of toddlers met the physical activity (99%) or sleep (82%) recommendation, those who met the screen time recommendation was only 15% (Figure 1).

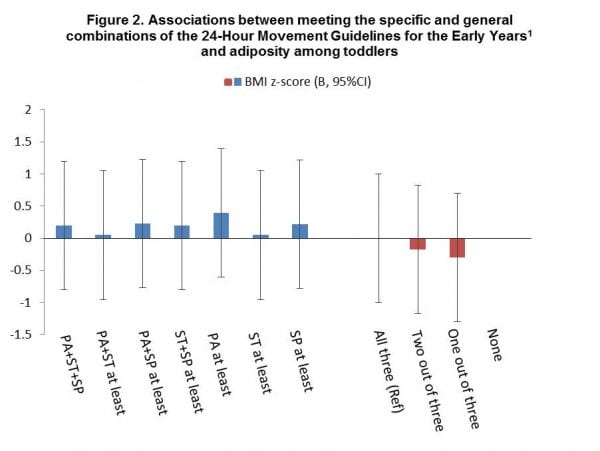

When the associations between meeting the specific and general combinations of movement behaviour recommendations and BMI z-scores were examined, none of the associations were found to be statistically significant (Figure 2).

Study results are in line with the findings of four systematic reviews that have informed the development of the new guidelines.2-5 Briefly, in contrast to more conclusive results in older age groups6-8, the associations between separate or combined movement behaviours and adiposity were mixed across studies.2-5 One potential explanation of the null findings is that it is difficult to observe conclusive associations among movement behaviours and adiposity in toddlers because it takes time for behavioural characteristics to lead to morbidity.9 In addition, the association between movement behaviours and the timing of adiposity rebound, in which BMI gradually declines after the first year of life until it reaches its lowest point around age 5 to 6 years of age, may also explain the null findings of our study.10, 11 For instance, high active compared to low active children may have later rebounds and subsequently higher BMIs during the early years period.12 Toddlerhood is a period of rapid development in motor, sensory, cognitive and social skills that bridges infancy and early childhood13; thus, developmental indicators other than the adiposity measure may be more relevant to this age group.

In this study, we found that the majority of toddlers are engaging in recommended amounts of physical activity and sleep but also are engaging in more screen time than recommended. Based on these findings, it is important to offer ways for parents and practitioners to limit toddler’s screen time to align with the guidelines. Therefore, future studies should identify correlates and patterns of screen time of toddlers in home and childcare settings respectively, to develop appropriate strategies to prevent or minimize the early exposure to screen based devices in this age group. This is one of the objectives of the PREPS study.

The published article on this study can be found here: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-017-4855-x

An infographic on this study is also available here: https://www.centre4activeliving.ca/news/2017/12/toddlers-meeting-24-hr-movement-guidelines/

References

- Tremblay MS, Chaput JP, Adamo KB, Aubert S, Barnes JD, Choquette L, Duggan M, Faulkner G, Goldfield GS, Gray CE, Gruber R. Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for the Early Years (0–4 years): An Integration of Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour, and Sleep. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(5):874.

- Carson V, Lee EY, Hewitt L, Jennings C, Hunter S, Kuzik N, Stearns JA, Unrau SP, Poitras VJ, Gray C, Adamo KB. Systematic review of the relationships between physical activity and health indicators in the early years (0-4 years). BMC Public Health. 2017;17(5):854.

- Chaput JP, Gray CE, Poitras VJ, Carson V, Gruber R, Birken CS, MacLean JE, Aubert S, Sampson M, Tremblay MS. Systematic review of the relationships between sleep duration and health indicators in the early years (0–4 years). BMC Public Health. 2017;17(5):855.

- Kuzik N, Poitras VJ, Tremblay MS, Lee EY, Hunter S, Carson V. Systematic review of the relationships between combinations of movement behaviours and health indicators in the early years (0-4 years). BMC Public Health. 2017;17(5):849.

- Poitras VJ, Gray CE, Janssen X, Aubert S, Carson V, Faulkner G, Goldfield GS, Reilly JJ, Sampson M, Tremblay MS. Systematic review of the relationships between sedentary behaviour and health indicators in the early years (0–4 years). BMC Public Health. 2017;17(5):868.

- Poitras VJ, Gray CE, Borghese MM, Carson V, Chaput JP, Janssen I, et al. Systematic review of the relationships between objectively measured physical activity and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41(6):S197–239.

- Carson V, Hunter S, Kuzik N, Gray CE, Poitras VJ, Chaput J-P, et al. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth: an update 1. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41(6):S240–65.

- Chaput J-P, Gray CE, Poitras VJ, Carson V, Gruber R, Olds T, et al. Systematic review of the relationships between sleep duration and health indicators in school-aged children and youth 1. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41(6):S266–82.

- Lee I-M. Current issues in examining dose-response relationships between physical activity and health outcomes. In: Lee I-M, editor. Epidemiologic methods in physical activity studies. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. p. 56–76.

- Moore LL, Gao D, Bradlee ML, Cupples LA, Sundarajan-Ramamurti A, Proctor MH, et al. Does early physical activity predict body fat change throughout childhood? Prev Med. 2003;37:10–7.

- Rolland-Cachera MF, Deheeger M, Maillot M, Bellisle F. Early adiposity rebound: causes and consequences for obesity in children and adults. Int J Obes. 2006;30(Suppl 4):S11–7.

- Moore LL, Gao D, Bradlee ML, Cupples LA, Sundarajan-Ramamurti A, Proctor MH, et al. Does early physical activity predict body fat change throughout childhood? Prev Med. 2003;37:10–7.

- Rathus SA, Christina RM. Childhood and adolescence: voyages in development. Toronto: Thomson Wadsworth; 2009.

About the author: Dr. Eun-Young Lee was a Post-Doctoral Fellow with the Behavioural Epidemiology Lab at the University of Alberta. She is currently continuing her post-doctorate training in the Healthy Active Living and Obesity Research Group at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute. Dr. Lee’s research focuses on studying the correlates and determinants of physical activity and sedentary behaviour and how they influence health and well-being among young people. You can find her on Twitter @DrEunYoungLee.

About the author: Dr. Eun-Young Lee was a Post-Doctoral Fellow with the Behavioural Epidemiology Lab at the University of Alberta. She is currently continuing her post-doctorate training in the Healthy Active Living and Obesity Research Group at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute. Dr. Lee’s research focuses on studying the correlates and determinants of physical activity and sedentary behaviour and how they influence health and well-being among young people. You can find her on Twitter @DrEunYoungLee.

This article has also been published on Obesity Panacea.