Sedentary Behaviour and Diabetes Information as a Source of Motivation to Reduce Daily Sitting Time in Office Workers: A Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial

May 7, 2020

A Combined Health Action Process Approach and mHealth Intervention to Increase Non‐Sedentary Behaviours in Office‐Working Adults—A Randomised Controlled Trial

May 20, 2020Today’s post comes from Amanda Lien, an MPH student at the University of Guelph, describing her recent study, “Adherence to 24-hour movement guidelines and academic performance in adolescents”, that was recently published in the Public Health journal (available here).

Lien A, Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Colman I, Hamilton HA, Chaput J-P. Adherence to 24-hour movement guidelines and academic performance in adolescents. Public Health 2020;183:8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.03.011.

Background

The Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for children and youth are defined as:

- 60+ minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity per day

- No more than 2 hours of screen time per day

- 9-11 hours, 8-10 hours, and 7-9 hours of sleep per day for ages 11-13 years, 14-17 years, and 18 years or older, respectively

In isolation, relationships between the behaviours of the Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines (sleep, screen time, and physical activity) and academic performance have been explored. Poorer academic performance was seen with more than 2 hours of daily TV viewing and possibly with shorter sleep duration.

Our Study

We conducted a cross-sectional study to examine the association between meeting combinations of the 24-hour movement guidelines and academic performance by performing a multiple linear regression of a sample of 10,160 grade 7-12 students that completed the 2017 Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey.

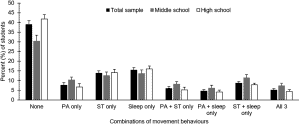

Our analysis found that more middle school students met each of the guidelines than high school students, with 33.5% of all students meeting the screen time guideline, 23.1% meeting the physical activity guideline, 33.8% meeting the sleep guidelines. Overall, 5.1% of students met all guidelines and 39.0% met none of the guidelines.

Among middle school students, better academic performance was observed with meeting either the screen time guideline only, sleep guideline only, or all three guidelines. Among high school students, better academic performance was observed with meeting both the sleep and screen time guidelines without adherence to the physical activity guideline.

Interestingly, we did not observe a dose-response relationship between the number of guidelines met and academic performance, which stands in contrast with various studies that have examined the relationship between meeting combinations of the guidelines and physical health indicators and cognition. This may be partly explained by the time component of academic performance. Unlike physical health indicators and cognition, academic performance is largely dependent on time spent on activities such as completing homework and studying. Therefore, activities such as watching TV and playing video games compete with and can take away time that would otherwise be spent partaking in activities that might enhance academic performance.

This rationale may also explain the lack of association observed between meeting the physical activity guideline and academic performance in high school students. For instance, high school students meeting but also exceeding the recommended 60 minutes of daily physical activity may allocate less time to their studies. That being said, meeting all three guidelines was associated with higher academic performance in middle school students, which is reasonable seeing as the time and effort that is required to succeed is greater in high school courses. Therefore, as academic performance becomes more dependent on time invested in educational activities (i.e. transitioning from middle school to high school to university), we would expect that beyond particular thresholds, an inverse relationship between academic performance could be observed with increasingly large amounts of screen time or physical activity.

Because the associations observed in our study were weak, further studies are required to establish any short- or long-term cause-and-effect relationships. However, our findings indicate the importance of taking a balanced approach to helping adolescents obtaining beneficial amounts of sleep, screen time, and physical activity.

About the Author

Amanda Lien is a Masters of Public Health student at the University of Guelph, recently completing a practicum with the Public Health Agency of Canada, where her focus was the surveillance of laboratory incidents and laboratory-acquired infections. Her interests also include the exploration and implementation of healthy active living lifestyles and interventions for youth and adolescents.