The time for pandemic uprising is here – let gravity be your friend!

April 15, 2020

Measures of sedentary behaviour: How do they compare?

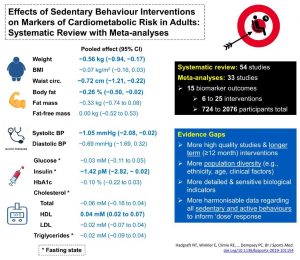

April 29, 2020Today’s post comes from Dr. Paddy Dempsey and colleagues, describing their new paper “Effects of sedentary behaviour interventions on biomarkers of cardiometabolic risk in adults: systematic review with meta-analyses”, which is available here (open access). You can find more about the authors at the bottom of this post.

In recent years, interventions to reduce sedentary behaviour in various settings, including the workplace, have become quite prevalent, in recognition of the potential risks of sedentary behaviour to cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. Systematic reviews evaluating their success have concluded that they do reduce sedentary behaviour, to varying degrees, but so far have yet to determine the extent to which these ‘real-world’ interventions provide the health parameters such as have been reported for acute laboratory interventions.

Accordingly, we conducted an extensive systematic review with meta-analyses of interventions targeting sedentary behaviour in free-living conditions for ≥7 days, alone or combined with physical activity. We specifically focused on their effectiveness for adults on biomarkers of cardiometabolic risk, particularly those related to body anthropometry, blood pressure and related haemodynamics, blood glucose and lipids, and inflammatory biomarkers.

What did we do?

We searched six electronic databases up to August 2019 for full-length publications in English language of studies with an intervention design (single-group, parallel-group, or crossover) that intervened on sedentary behaviour for ≥7 days, in human participants aged ≥18 years and reported on at least one biomarker of cardiometabolic health as per the list above. The meta-analyses, conducted by random effects models, considered all outcomes collected in >5 interventions and examined only interventions that had a corresponding control group, and did not provide other interventions (e.g., diet) apart from than shifting behaviour to more active forms.

What did we find?

54 studies (involving 56 interventions) were included in the systematic review. Mostly these had small sample sizes less than 100 (k=36), were conducted in North America (k=20), Europe (k=19), or Australia (k=10), intervened in the workplace (k=27) or community (k=18) settings, typically for less than 6 months (k=44) and in non-clinical populations (k=43). Overall, 33 studies (34 interventions) met the criteria for meta-analyses.

Pooled effects showed statistically significant (p<0.05), small benefits of intervention relative to control on weight, waist circumference, % body fat, systolic blood pressure, insulin and HDL cholesterol (see Infographic below). Pooled effects on the other biomarkers were non-significant, small, and in a direction indicating benefit, or no effect at all concerning fat-free mass (see Infographic). Hetereogeneity was observed for 8 of 15 of the outcomes, for which a number of factors emerged as relevant in meta-regressions, but with no consistent explanation for the variability in findings.

Gaps in the evidence base

Our critical review noted a need for more interventions that are longer-term (≥12 months), measure what happens after intervention ceases, recruit clinical populations (e.g., people with type 2 diabetes), evaluate dose and dose-response in terms of sedentary and active behaviours, and collect as outcomes inflammation, vascular function, and postprandial metabolism. Ideally, more of the studies should be high-quality; here, many had a ‘medium’ risk of bias.

The findings suggested certain population groups may be at greater risk of adverse health effects from sedentary behaviour, and different interventions may ameliorate this risk to a greater or lesser degree. As the evidence base grows, in future it may be possible to estimate the effectiveness of sedentary behaviour interventions specific to various intervention settings and/or components, and in various populations (e.g., men, women, older adults, adults with type 2 diabetes).

So what?

This review was possible following the recent emergence of several reasonably sized randomised trials (>200 participants), which is timely and important in view of the introduction of sedentary behaviour recommendations into contemporary physical activity guidelines and their ongoing refinement.

Our main finding — that sedentary behaviour interventions generate small improvements to selected biomarkers of cardiometabolic health under real-world conditions — provides complementary ‘triangulation’ to the growing body of evidence from observational research and acute (<7 day) interventions in laboratory conditions.

Collectively, the evidence supports the sedentary behaviour guidelines, but as yet cannot identify the specific effects that particular active and sedentary behaviours may elicit. Along with the other gaps identified by this critical review, this is a key consideration for future research in identifying priorities for sitting-reduction initiatives, and for optimising their benefits to cardiometabolic health.

Simple summary infographic

Citation

Hadgraft NT, Winkler E, Climie RE, Grace MS, Romero L, Owen N, Dunstan D, Healy G, Dempsey PC. Effects of sedentary behaviour interventions on biomarkers of cardiometabolic risk in adults: systematic review with meta-analyses. Br J Sports Med. 2020. Epub ahead of print: 2 April 2020. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2019-101154

About the authors

Nyssa Hadgraft is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Centre for Urban Transitions at Swinburne University of Technology (Melbourne, Australia). Her research interests include understanding the multi-level influences on physical activity and sedentary behaviour as risk factors for chronic disease, with a particular focus on the workplace setting. You can connect with Nyssa via twitter or email.

Elisabeth Winkler is a Data Analyst at the School of Public Health at The University of Queensland (Brisbane, Australia). Her research interests include evaluating behaviour changes (particularly sedentary behaviour, physical activity and nutrition) in relation to each other, their precursors and their sequelae. You can connect with Elisabeth via email.

Paddy Dempsey is a Research Fellow at the University of Cambridge (UK) and the Baker Heart & Diabetes Institute (Melbourne, Australia). His research interests are currently focussed on the role of sedentary behaviour, physical activity and diet (including their interacting effects) in the prevention and management of chronic diseases, particularly type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. You can connect with Paddy via twitter or email.