Popularity or Pathology? Internet Addiction and Gaming Disorder

June 17, 2019Post-Doctoral Opportunity in Brazil

June 18, 2019Today’s post comes from Dr Peter Katzmarzyk. More info on Dr Katzmarzyk can be found at the bottom of the post.

When the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, Second Edition were released in late 2018, they included recommendations for decreasing sedentary behavior in addition to increasing moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity levels. 1 The inclusion of sedentary behavior in the new guidelines was prompted by the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report which provided evidence on the health effects of sedentary behavior, and on the interactions between sedentary behavior and physical activity on health outcomes.2, 3

Despite the mounting evidence on the health concerns associated with sedentary behavior that has been published over the last decade, the incorporation of sedentary behavior into the new U.S. Guidelines was never a guaranteed outcome. Indeed, there was some spirited debate among the Committee members as to whether or not sedentary behavior should be included in “physical activity” guidelines. In the end, sedentary behavior was considered an important component of the new U.S. Guidelines; mainly focusing on the interactions between sedentary behavior and physical activity, and the role of sedentary behavior in affecting the amount of physical activity needed to achieve health benefits. In other words, does the recommended amount of physical activity differ according to the amount of daily sitting a person experiences? The answer it turns out is “yes”!

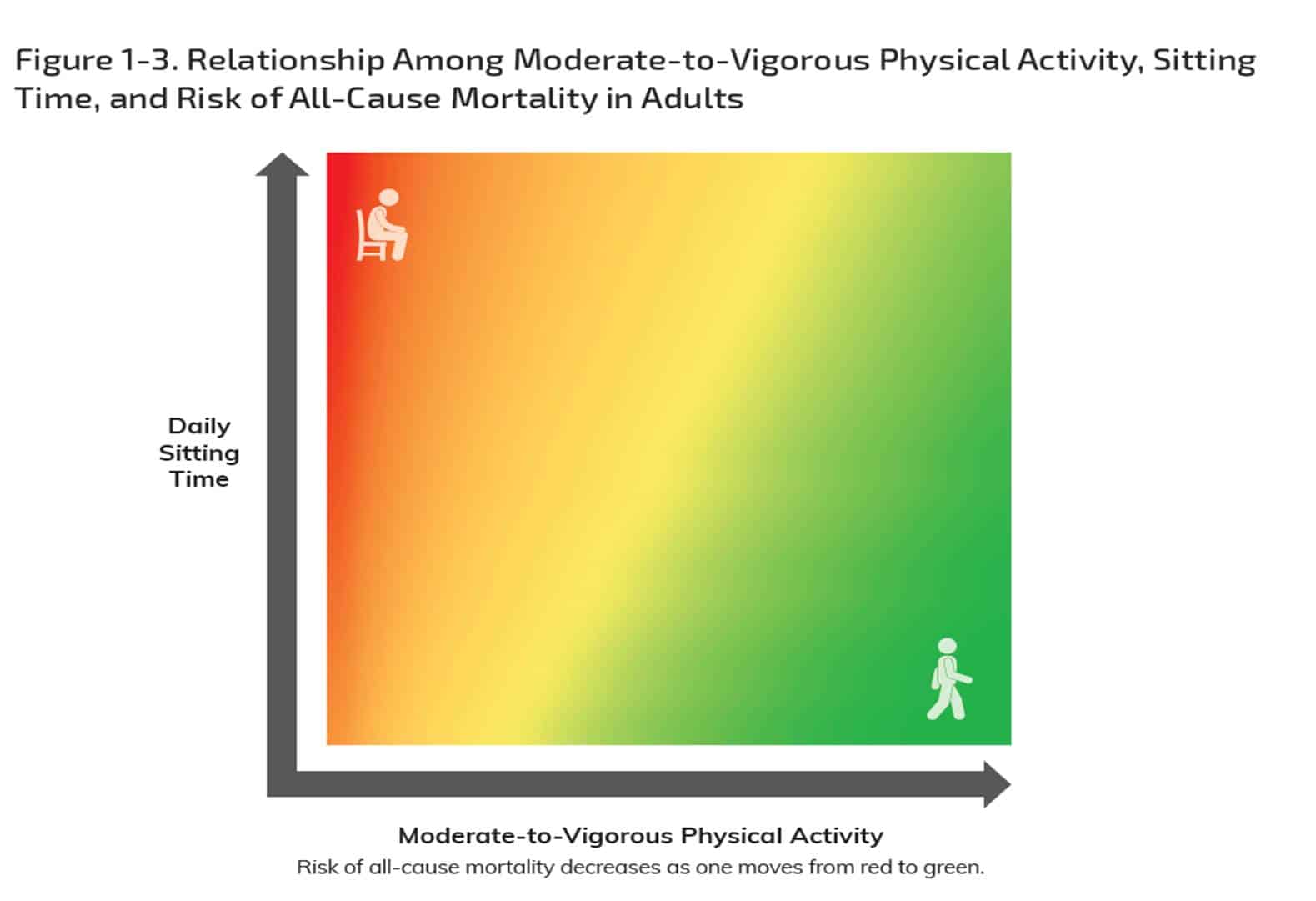

Several prospective cohort studies have documented interactions between sedentary behavior and physical activity on all-cause mortality rates. These data were combined and analyzed in a provocative meta-analysis by Ulf Ekelund and colleagues.4 The results demonstrated that in people with high sitting time, high levels of moderate-intensity physical activity (60-75 minutes per day) are required to eliminate the associated increased risk of death. The Committee relied heavily on these results and developed a heat map (see Figure) which conveys the risk of mortality associated with different combinations of sitting and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. Briefly, at low levels of sitting, less physical activity is required to move into the green (lower risk of mortality); whereas at high levels of sitting, much more physical activity is required to achieve the same level of mortality risk.

Figure 1.3 from the 2nd Edition of Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, available here.

While the U.S. has integrated sedentary behavior into their physical activity guidelines based on interactions with physical activity, other countries have also included information on certain sedentary behaviors (i.e. screen time) alongside their physical activity guidelines for children and youth. For example, Canada initially released separate (from physical activity) sedentary behavior guidelines for children and youth5 which have subsequently been replaced by 24 hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Youth6 (physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep) that have been adopted by Australia.7 The 24-hour guideline concept has been extended into the pre-school age range in Canada,8 Australia9 and most recently by the World Health Organization.10 The rationale for combining guidelines on physical activity, sedentary behavior and sleep is that each day is constrained by the 24-hour period, and these three movement behaviors make up that 24-hour period. It makes sense to address all three behaviors in one comprehensive set of guidelines rather than keeping them separate.

Whether sedentary behavior makes its way into physical activity guidelines based on interactions with health outcomes, or by the rationale that the “whole day counts”, it is my opinion that valuable information is gained by doing so. From an energy expenditure point of view, sedentary behavior lies on the low end of the physical activity spectrum; however, sitting and moderate-to vigorous physical activity represent two distinct behavioral targets that can be addressed to improve public health – the “sit less – move more” message may begin to resonate with the public and may have long term public health impacts. Time will tell.

About the Author

Dr. Katzmarzyk is Professor and Associate Executive Director for Population and Public Health Sciences at the Pennington Biomedical Research Center where he holds the Marie Edana Corcoran Endowed Chair in Pediatric Obesity and Diabetes. He recently served on the 2018 U.S. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Dr. Katzmarzyk is Professor and Associate Executive Director for Population and Public Health Sciences at the Pennington Biomedical Research Center where he holds the Marie Edana Corcoran Endowed Chair in Pediatric Obesity and Diabetes. He recently served on the 2018 U.S. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

References

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd Edition. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2018.

- 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2018.

- Katzmarzyk PT, Powell KE, Jakicic JM, Troiano RP, Piercy K, Tennant B. Sedentary behavior and health: Update from the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019; 51(6): 1227-41.

- Ekelund U, Steene-Johannessen J, Brown WJ, Fagerland MW, Owen N, Powell KE, et al. Does physical activity attenuate, or even eliminate, the detrimental association of sitting time with mortality? A harmonised meta-analysis of data from more than 1 million men and women. Lancet. 2016; 388: 1302-10.

- Tremblay MS, Leblanc AG, Janssen I, Kho ME, Hicks A, Murumets K, et al. Canadian sedentary behaviour guidelines for children and youth. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2011; 36(1): 59-64.

- Tremblay MS, Carson V, Chaput JP, Connor Gorber S, Dinh T, Duggan M, et al. Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Youth: An integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016; 41(6 Suppl 3): S311-27.

- Australian Government, The Department of Health. Australian 24-Hour Movement Guigelines for Childre (5-12 years) and Young People (13-17 years): An Integration of Physcal Activity, Sedentary Behavior, and Sleep. Available at: https://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/ti-5-17years 2019.

- Tremblay MS, Chaput JP, Adamo KB, Aubert S, Barnes JD, Choquette L, et al. Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for the Early Years (0-4 years): An Integration of Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour, and Sleep. BMC Public Health. 2017; 17(Suppl 5): 874.

- Okely AD, Ghersi D, Hesketh KD, Santos R, Loughran SP, Cliff DP, et al. A collaborative approach to adopting/adapting guidelines – The Australian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for the early years (Birth to 5 years): an integration of physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep. BMC Public Health. 2017; 17(Suppl 5): 869.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior and Sleep for Children Under 5 Years of Age. Geneva; 2019.